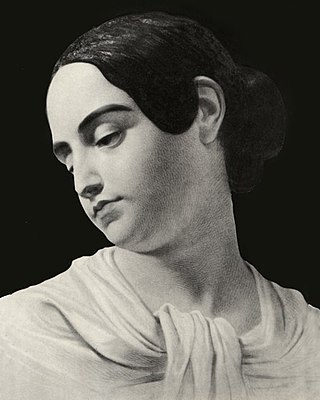

I was reading recently about mourning portaiture, specifically the photographic preservation of a person after death – a type of death mask. To some this seems gruesome, but I’ve always found it intuitively, emotionally sensible. We are creatures of artifact, and this is no less so with those we love than with our Things and our Stuff. I have a refrigerator magnet – a lovely portrait of a lady – which nobody has ever remarked upon. It’s a miniature reproduction of the death portrait of Virginia Clem Poe, the mother of Edgar Allen.

|

| Virginia Clemm Poe Image: Wikimedia |

I keep this not only because Poe is a native son and I grew up on his writing, but because it’s beautiful – and, yes, the fact of her death is a part of that. For me, this isn’t a morbid thing – death is a part of life, and though my culture has lost sight of that (indeed, pushed the sight away, for a century or so), I find its denial bewildering and unnecessary.

It’s not an arch matter of art or self-image, either. I don’t think about death with particular emphasis, and my memory of those I have loved who have died – or who face death – is not mystical nor romantic.

Yet when I see the story of a man in mourning, who asked people to provide an image of his child, unencumbered by the medical paraphenalia which marked her all-too-brief life, I see the resulting mourning images of her as the most immensely human impulse we have. To reach out to one another in good faith, to share and to support. It would be despicable to look at the images strangers produced, and rank them for skill or merit – to dismiss them as gross – or as revisionism – to make the story of this infant in any way “about myself” by presuming my opinions onto anything about them. They are the shared emblem of the most deeply personal grief.

It is when we share the deeply personal that humanity allows itself to transform intensely intimate fear and sadness into the most essential form of community available to us – the manifestation that what we suffer is more important than what we *make* each other suffer, or *desire* each other to suffer … or even to enjoy. It is when we take what is our own, and show it – share it – that loss becomes healing, that desolation gains meaning, and we become again part of something beyond ourselves, our experiences. In loss, we can forget we are not alone (many of us seek isolation in sorrow). And that is when individual loss convinces us we’re not human like everybody else. And that is when, more than merely losing one we loved, we degrade the love they gave us in return, by denying it with anybody else.

Memorializing human bonds by perverting them, denying them, destroying them … is no way to repay the blessing of having ever had a bond at all.

|

| The First Mourning Image: Wikimedia |

No comments:

Post a Comment